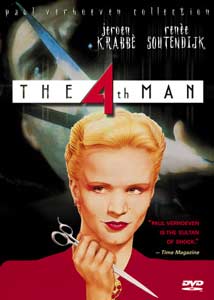

The 4th Man

After a consideration of his filmography, even detractors must note that few filmmakers are as brazen as Paul Verhoeven. Though he might not give utmost consideration to the depth of a character, he will always try to combine entertainment with a consideration of intellectualism. That is, though he clearly prides himself on his work as producer of entertainment, he wants to work with film as a duplicitous medium as well, analyzing paranoia and delusions as a characteristic of the human condition, even if he shortchanges that analysis on occasion.

After a consideration of his filmography, even detractors must note that few filmmakers are as brazen as Paul Verhoeven. Though he might not give utmost consideration to the depth of a character, he will always try to combine entertainment with a consideration of intellectualism. That is, though he clearly prides himself on his work as producer of entertainment, he wants to work with film as a duplicitous medium as well, analyzing paranoia and delusions as a characteristic of the human condition, even if he shortchanges that analysis on occasion.With The 4th Man (1983), however, he bridges those two ideals fairly evenly, allowing a consideration that rises above the dualism of humanity that is suggested in the opening symbolism with a spider climbing over a statue of Jesus. While some might view this as simple lip-service to Bergman’s metaphor in his religious chamber trilogy, it’s paramount to a thematic consideration of the hybridity, rather than mere dualism, of The 4th Man, for the film seeks to undermine these notions of either/or with its analysis of Christine Halsslag (Renée Soutendijk), a woman who can initially be viewed as causing the murder of her previous husbands or be viewed as a helpless pawn in life’s misfortune. This accusatory viewpoint is complicated in the paranoia of our protagonist, Gerard Reve (Jeroen Krabbé).

Between Gerard’s paranoia and delusions, Verhoeven creates an indeterminancy that adds greater psychological weight to the affair and makes the story into more than a film noir and femme fatale picture. Verhoeven’s aesthetic is perfect for a scene in which Gerard learns of the fates of Christine’s previous spouses vis-à-vis a film projector, and Gerard’s simultaneous disgust and intrigue is matched by own captivation for how Verhoeven manipulates his sordid material. And though Bergman analogies are a bit heavy-handed, they are overall in tune with the goals of the film and work in nice contrast to the Mary metaphors. Very good stuff, and it features some very interesting expansions into film noir, specifically a treatment of homosexuality and androgyny within the genre.