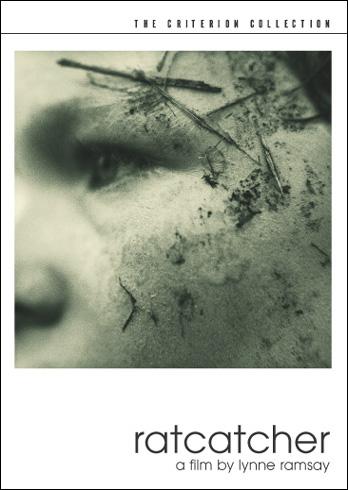

Ratcatcher

Lynne Ramsay’s Ratcatcher (1999) is perhaps the biggest surprise on this list for me. It was one of the last additions, largely because I kept deliberating on what makes this film so different from other stories about preadolescent males who grow up amidst poverty, secrecy, and self-reflective guilt. Ultimately, it comes down to how Ramsay eschews conventionality to tell a more panoramic case study, allowing the narrative to unfold naturalistically, yet with flair and elegance, so that Ratcatcher becomes a document of an entire city seen through the extremely subjective viewpoint of one boy.

Lynne Ramsay’s Ratcatcher (1999) is perhaps the biggest surprise on this list for me. It was one of the last additions, largely because I kept deliberating on what makes this film so different from other stories about preadolescent males who grow up amidst poverty, secrecy, and self-reflective guilt. Ultimately, it comes down to how Ramsay eschews conventionality to tell a more panoramic case study, allowing the narrative to unfold naturalistically, yet with flair and elegance, so that Ratcatcher becomes a document of an entire city seen through the extremely subjective viewpoint of one boy.And immediately the film announces its narrative subversions as our expected protagonist drowns in the early minutes of the film, settling upon the guilt that James (William Eadie) finds himself plagued with, internalizing feelings of the waste and wreckage that sit alongside the Glasgow homes during the 1970’s garbage strike that the film is based in. Yet James finds security in his escapes of reverie out into the countryside, where wheat fields and empty houses show him a promise and allure that is entirely beyond impoverished family. Moreover, Ramsay fashions a facsimile of an adult relationship between James and Margaret Anne (Leanne Mullen), as the two are appropriately confused and understanding of the responsibilities that attraction and adulthood are supposed to bring. There is an understated reciprocity in a scene in which the two bathe one another, and if they nonetheless draw away from one another, it’s because neither James nor Margaret Anne have a good same-sex parental figure to emulate.

The film reveals itself to be a marvel during a sequence in which his friend Kenny ties his newly purchased mouse to a balloon and releases her from his upper-level apartment. The extended sequence that follows was a transcendent moment, full of narrative and creative aplomb. Likewise, and in a moment that reminds me of the similarly-minded tranquility that exists, albeit briefly, in Lukas Moodysson’s A Hole in My Heart, James’ trips through the countryside are the respite to his habitual oppression in his familial life. Throughout Ramsay and her composer Rachel Porter find a quiet lyricism to alleviate the bleakness, resulting in a poetic masterpiece of mood and character, with an appropriately ambiguous ending.

Ratcatcher: 10/10

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home