Woody Allen's

Husbands and Wives (1992) is Allen’s masterpiece from the 1990s, critiquing marriage as an institution that works best when couples embrace their passivity as a necessity for the marriage to work. Beneath that passivity, though, many undercurrents of guilt and repressed anger lie ready to be unleashed at the uninitiated. All of these emotions find release within the story of two couples, Gabe Roth (Woody Allen) and his wife Judy (Mia Farrow), and Jack (Sydney Pollack) and Sally (Judy Davis), with the latter couple initially embracing time apart and the former threatened by the possibility of separation.

This film seems most in tune with Jean-Paul Sartre’s famous ending to his play, No Exit, wherein one of the characters trapped in a locked room, which is itself a metaphor for the stasis of hell, suddenly realizes that “Hell is—other people.” In that play, characters once in love turn on one another, spurning each other in sudden flurries of contempt. Like the Sartre play, Allen’s characters are ensnared in a slow burn, where petty deceits suddenly become something much more traumatic and real, and are unleashed in incandescent fits of rage.

For their part, Jack and Sally are in a marriage of emotional paralysis. Jack finds that he cannot be sexual with his emotionally frigid wife, nor can he be free to enjoy the simple life since Sally is constantly critiquing something or other. When the two split, Jack resurfaces with the much younger Sam, an aerobics instructor who is not intellectually stimulating but nonetheless a woman who offers Jack the simple life. For her part, Sally maintains the façade of comfort in her new conditions as a single woman, but is emotionally crippled by Jack’s abandonment. Though each embraces time apart from the other, they eventually find that they are most comfortable around one another, even if much of that time is hounding each other. Moreover, it is only once Jack and Sally are no longer together that they can finally be honest with one another. As a result, on some level the separation leads to better communication, though a deeper reality lies in the realization that they are simply repressing any negative aspects of their marriage from here on out.

Meanwhile, Gabe and Judy soon find the seams of their relationship fraying from insecurity and charges of dishonesty. Each begins to be attracted to another, Gabe with one of his college students Rain (Juliette Lewis) and Judy with her colleague Michael (Liam Neeson). Though neither actively engages in infidelity, Allen suggests that each spouse is still using the interest that the third party shows in them to string them along until they are more sure of their emotions. As such, Gabe lends Rain his novel in progress and Judy lends Michael poems that she’s written, and Allen is quick to imply that Gabe and Judy both profit from their creative art by using it as a conduit to jumpstart their affairs.

Eventually, Gabe and Judy separate even as Jack and Sally reconcile, implying that some marriages can be rectified by repression, whereas others will simply wither and fade as spouses entertain the fantasies of being with another. Throughout this all, we come to understand Gabe’s declaration that he seems preternaturally interested in “kamikaze women,” women who lead Gabe into self-destruction with them. It is in the film’s conclusion that this idea is subverted, since Judy ends up with Michael (even though he settles for her even as he’s most excited by a brief relationship he once had with Sally), while Gabe ends up alone, unable to carry through with an affair with Rain. There is some small epiphany there for Gabe, as he renounces the inevitable flame of Rain, refusing to carry out a relationship that will fail just as his last one did. And while Allen is a pessimist, the idea of marriage is given a redemptive realization vis-à-vis Rain’s parents, who exhibit positive affection for each other. Within those couples unable to generate honest and open communication, though, the concept of marriage is tied to slow and mutual disintegration.

Since this is all framed within the parameters of a documentary, with a camera whipping around trying to capture those moments most paramount to their lives, it initially comes as a mild surprise that the documentary makers do not grasp that they are not just filming these moments of abandonment but are also contributing to it through their invasive techniques. While this may be read simply as a critique on the media’s interest in tearing down those it intends to profit from, there is another level at which the metaphor works, since it also commentates upon the nature of all cinema and how such an invasion upon simple “characters” inevitably brings to the surface their inadequacies and shortcomings.

Husbands and Wives: 10/10

Peter Greenaway's A Zed and Two Noughts (1985) is a meticulous study on the effects of loss and trauma filtered through scientific examination. In our twin protagonists’ obsessive effort to maintain control over the uncontrollable effects of life and the natural world, they compartmentalize the trauma they suffer when they lose their respective wives in a freak car accident with a white swan. Inasmuch as they find solace in their work, turning to an obsessive examination on the study of decay in animals, they likewise find a counterpart in the woman who was driving the car which killed their spouses.

Peter Greenaway's A Zed and Two Noughts (1985) is a meticulous study on the effects of loss and trauma filtered through scientific examination. In our twin protagonists’ obsessive effort to maintain control over the uncontrollable effects of life and the natural world, they compartmentalize the trauma they suffer when they lose their respective wives in a freak car accident with a white swan. Inasmuch as they find solace in their work, turning to an obsessive examination on the study of decay in animals, they likewise find a counterpart in the woman who was driving the car which killed their spouses.

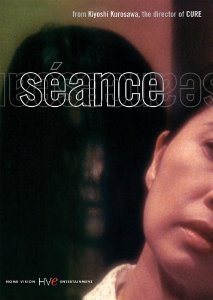

Kiyoshi Kurosawa's

Kiyoshi Kurosawa's