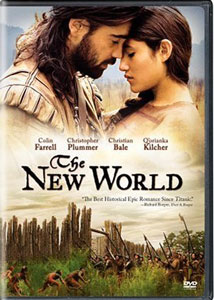

The New World

Terrence Malick’s films have always been about the struggle for wholeness, redemption, and transcendence, with the image being linked to startling revelation vis-à-vis music or voiceover rather than traditional plot. In The New World (2005) more so than any of his other films plot is incidental, which for some generates a disinterest as the most formal of cinematic devices is shed, yet the plot, such as it is, is still advanced through thematic considerations and circular, modulated images.

Terrence Malick’s films have always been about the struggle for wholeness, redemption, and transcendence, with the image being linked to startling revelation vis-à-vis music or voiceover rather than traditional plot. In The New World (2005) more so than any of his other films plot is incidental, which for some generates a disinterest as the most formal of cinematic devices is shed, yet the plot, such as it is, is still advanced through thematic considerations and circular, modulated images.This is a film that masks its observation of the Indians in transcendentalist musings, sifting through Captain John Smith’s (Colin Ferrell) voiceover that reveres the harmony of the native people. Yet in the same manner that Private Witt in The Thin Red Line idealized the island people and believed there to be no inner conflict or animosity, here we find Smith similarly romanticizing. We later understand that conflicts are if not constant, then they are at the very least chronic, and it is Smith, and not Malick, who fails to consider this reality. Likewise, Rebecca/Pocahontas (Q’Orianka Filcher) finds her father casts her out of the tribe because of the Europeans’ betrayal, which she has helped foster, and so here as well Malick refuses to sentimentalize the natives. We also receive the critique that the men with power (here the colonialists) seek to remake new worlds in the image of their own, to the detriment of those already peopled there.

In the film, action is often viewed through objects/doorways that filter and obstruct the totality of one’s vision, allowing for a romantic and idealized interpretation of what one sees, which allows Malick the opportunity to mix naïve romanticism with a more critical and judicious eye. For instance, in the opening we find Captain John Smith chained below the deck since the crew had already mutinied, and his vision of the new world is filtered through the tiny window that he gazes out of. Similarly, this same idea will later be seen and modulated when John Rolfe (Christian Bale) gazes upon Rebecca / Pocahontas through a doorway and fetishizes her beauty as opposed to realizing her lingering attraction to Smith, as well as in other instances.

Ultimately, this film becomes a consideration of what Pocahontas is meant to be read as—is she to be seen as Indian or European, or does she exist beyond the parameters of either/or? Though her freedom is most celebrated when she is in her Indian apparel, the film is not locked into an idea that she is caged after she is brought to Jamestown and Europeanized. Once she has born a son to her husband and becomes Europeanized, similarly to how North America is Europeanized, are we to feel betrayed, resentment, or gratitude? Ultimately, despite the romanticism of the natives, it must be decided that Malick celebrates and understands both the benefits and restrictions that followed such a move, and the vestiges of the past make way for the wholeness of the present.

For me personally, there have been few experiences as great as seeing The New World on the big screen twice, letting the film’s emotions wash over me in both small waves and large crescendos. Serving as the opening, middle, and climax of the film, the prelude to Wagner’s “Das Rheingold” receives the same transcendent treatment that Kubrick gave Richard Strauss’ “Thus Spake Zarathustra” in 2001, creating a poem of music and images that cumulatively leaves me euphoric after every viewing.

The New World: 10/10

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home