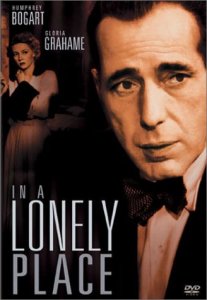

In a Lonely Place

Nicholas Ray's In a Lonely Place (1950) is a film that realizes the intersection between emotional passivity and narcissistic aggression is indeed a thin line. While the film initially feels like a noir piece, it truly is not, for Ray has no real interest in exploring hard-boiled and empty characterizations as such; rather, Ray seeks to understand how that emptiness may be misunderstood by a society dependent on the expression of sympathy and pity toward the dead.

Nicholas Ray's In a Lonely Place (1950) is a film that realizes the intersection between emotional passivity and narcissistic aggression is indeed a thin line. While the film initially feels like a noir piece, it truly is not, for Ray has no real interest in exploring hard-boiled and empty characterizations as such; rather, Ray seeks to understand how that emptiness may be misunderstood by a society dependent on the expression of sympathy and pity toward the dead.Dixon Steele (Humphrey Bogart) is a hard-drinking and down-on-his-luck screenwriter who becomes incriminated by the police when a young woman who helps him understand his next adaptation is murdered on her way home. His next door neighbor, Laurel Gray (Gloria Grahame), provides him with an alibi and the two begin to bond emotionally as they realize that their checkered pasts can be mediated by the love that each nurtures for the other. However, Laurel starts to see glimpses of Dixon’s violent past, and the film examines how a glimpse of violence can lead to potentially more damaging instances of aggression, so that Laurel’s sureness of Dixon’s innocence in the murder now becomes fraught with doubt and insecurity.

This is a film that has been observed as possessing one of cinema’s most upfront portrayals of existentialism, in that our protagonist played by Bogart shows a complete lack of empathy and understanding toward a death that society demands must be publicly mourned. As such, the internal conflicts of personality governed by a past in WW2 and occasional bar fights are now judged by the outward arbitrating eye of the society as law. Yet Ray wishes to question how society can judge the proper affect that is shown toward victims of tragedy, working to elucidate how even those who display an outward disregard are still nonetheless human and not deserving of a public outcry.

When Laurel and Dixon become engaged, Dixon’s past aggressions seem to be repressed for good. Yet even that repression does not altogether eliminate any trace of what has been “forgotten,” in that the dominant aspects of Dixon’s personality surface in emotionally troubled instances. It is here that the film’s mantra, uttered by Dixon in reference to working the line into the screenplay, becomes the primal epitaph of the film: “I was born when she kissed me. I died when she left me. I lived a few weeks while she loved me.”

This is a film that richly deserves to be seen more, and it rewards the interest that the audience places in it. Always engaging, always revealing. A masterpiece.

In a Lonely Place: 10/10

1 Comments:

Yeah this movie was Amazing! Made me want to start smoking!

Post a Comment

<< Home