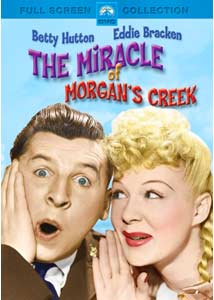

Miracle of Morgan's Creek

Much like his earlier films The Lady Eve and Sullivan’s Travels, Preston Sturges’ Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944) is an entertaining melodrama and exercise in rapid-fire comedy, though it is a film that, if the viewer is lacking in metatextual knowledge, initially seems devoid of any ties to reality. That is, this is a film so reliant on absurdity that it is only after understanding what Sturges attacks (specifically, the Hays Code’s restrictions upon cinema) vis-à-vis the film’s themes that the true wonder and appreciation for the film becomes known.

Much like his earlier films The Lady Eve and Sullivan’s Travels, Preston Sturges’ Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944) is an entertaining melodrama and exercise in rapid-fire comedy, though it is a film that, if the viewer is lacking in metatextual knowledge, initially seems devoid of any ties to reality. That is, this is a film so reliant on absurdity that it is only after understanding what Sturges attacks (specifically, the Hays Code’s restrictions upon cinema) vis-à-vis the film’s themes that the true wonder and appreciation for the film becomes known.None too bright Trudy Kockenlocker (Betty Hutton) is a small town girl who just wants to have fun with the American soldiers before they are sent overseas. Consequently, she flippantly rejects the attraction that dorky Norval Jones (Eddie Bracken) seeks to bestow upon her, abdicating any desire to him. Such a renouncing takes place until she wakes up married and impregnated the morning after a night out on the town, when she (literally) hits her head on a lamp but (symbolically) was drunk from a spiked drink. After that she and her prodigious younger sister Emmy (Diana Lynn) try to fashion a workable excuse, including marrying Norval (which Trudy can’t do because she’s too kindhearted to hurt Norval). And after all that we still haven’t arrived at the “miracle” behind the title.

Sturges continually offers the juxtaposition of obvious vs. latent intent, corrupting the characters with implied controversial ideas yet maintaining the air of innocence, and the way in which he manipulates our central emotions about the easygoing Trudy is perhaps the clearest example. Norval truly loves her but her first reaction to him is to maneuver his affection to her own advantage. Though my opinion of Trudy isn’t as appreciative as others, I respect how Sturges finagles and appropriates our conception of Trudy.

Unlike earlier Sturges films mentioned above, however, the most entertaining characters are not the main characters but rather the supporting cast. Because everyone is pretty much playing a caricature, it’s dependent on those actors who most embody their characters to give the film its comedic potential. For their part, the politicians fielding the small town’s phone call offer a nice amount of the hilarity, constantly usurping the hypocritical authority of the community (re: the Hays Code), and the Kockenlocker father (William Demarest) adds an edge that is simultaneously eyeroll-worthy and genius in its mockery of the stereotypical father, especially when he’s trying to convince the rather simpleminded Norval to knock him out in self-defense.

Yet the very fact that such knowledge (once obvious to its contemporary audiences but now steeped in a tradition of film history) is necessary to appreciate the hyper-caricatures and mockery of the Hays Code precludes more than just a bit of my enjoyment. This is not to say that preliminary legwork isn’t needed prior to watching a film, but rather this is to say that without such knowledge this film loses all basis in reality and instead becomes a lightweight comedy and not the hyper-critical attack on misguided censorship that Sturges truly wants it to be.

Miracle of Morgan's Creek: 7/10