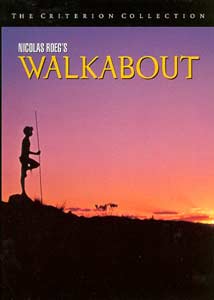

Walkabout

Few films are as hypnotically constructed as Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout (1971), a film that irrevocably details the shattering of childhood innocence, the implacable relationship of man to nature, and the solace that is found in cultural strangers who are nonetheless linked by their will to survive. This is a film that refuses to conform to rigid expectations of genre, often confounding our sensibilities by leaving secondary characters’ motivation anonymous, so that we can only determine scenes by the narrow subjectivity that guides the camera. It is an ingenious move, lending the film a sense of mystery and awe that allows the themes to exist at a more organic level.

Few films are as hypnotically constructed as Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout (1971), a film that irrevocably details the shattering of childhood innocence, the implacable relationship of man to nature, and the solace that is found in cultural strangers who are nonetheless linked by their will to survive. This is a film that refuses to conform to rigid expectations of genre, often confounding our sensibilities by leaving secondary characters’ motivation anonymous, so that we can only determine scenes by the narrow subjectivity that guides the camera. It is an ingenious move, lending the film a sense of mystery and awe that allows the themes to exist at a more organic level.The film follows a young 14-year-old girl (Jenny Agutter) and her 6-year-old brother (Luc Roeg) who are abandoned in the Australian outback by their father, a man who appears to have a nervous breakdown, shoots at them, and commits suicide during an afternoon picnic. These scenes unfold with the murky ambivalence of the unknown, leaving the girl to help her brother to fend for themselves in the outback and hope to survive until civilization can find them. They stumble upon a teenage aborigine boy (David Gulpilil) who is transitioning into adulthood by surviving on his own. The three form a kinship based on something beyond language and begin to take pleasure in the autonomy that they possess, fashioning a selfhood out of their predicament.

Yet this isn’t to say that Roeg isn’t critical of the cultural gap that exists between the three. While the White boy and the aborigine are able to express themselves with clarity and understanding, the girl and the aborigine lack this same ability, since the relationship is constricted by her more adamant subconscious demand that language conform to her more rigid definition of it. Here we see traces of sociopolitical and cultural critique from Roeg, in that the girl’s hesitance to bond linguistically with the aborigine harkens back to her upper-middle class upbringing. Likewise, the camera lingers on the girl’s body sensually at times, a move suggestive of the camera’s shift toward the aborigine’s subjectivity, yet the girl adamantly rebukes his attempts at courtship, preferring to remain chaste as opposed to shift toward the irrevocability of mature adulthood.

This is a film filled with long meditative passages unfurling themselves organically, creating contrasts and rhythms that extend the themes of the lead characters. Scenes of everyday nature are often intercut with scenes of mundane survival of the three, and the film is likewise conscious of the inevitability of the events of life, crosscutting between the aborigine’s carving of a kangaroo and the butcher’s carving of meat ready to be sold. When the three discover an abandoned house that is close to civilization, the film begins its push toward externalizing the sadness and mourning that has been internal for much of the film, leading to the aborigine’s suicide. This is the moment that defines the film, yet it too is shrouded in mystery.

The film concludes with the girl, now in adulthood and presumably married, looking back in reflection at this time of childhood as a return to the primal beauty and wonder she once knew, reminiscing when the three could swim naked and delight in their innocent play in lakes, when life was still a reservoir of untapped potential. It is this melancholy that affixes itself to Roeg’s film, and it is this melancholy that grants the film its greatest strength. A masterpiece of meditative cinema.

Walkabout: 10/10

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home